1. Introduction

University education has always adapted to society’s demands and, at the same time, has become one of the driving forces of change. However, the digital age has created a genuine break with the past due to demands for new roles, structures and trends. The introduction of new forms of communication and technologies for teaching and learning offers many innovative possibilities to increase the quality of teaching and learning processes and better adapt them to the characteristics of students (García Portillo, Romo, & Benito, 2008).

In order to increase the efficiency of the university system, relevant assessments of each of its component fields (teaching, management and research) are performed. In many cases, these evaluations are done through a variety of indicator systems, thus causing a lack of consensus on what to evaluate (results, process, teaching, etc.) and how to evaluate it (qualitative, quantitative, specific, general or other types of indicators) (Palomares, Garcia, & Castro, 2007).

The massification of university classrooms and the devaluation of teaching as compared to research have led to teachers looking for more responsive evaluation instruments closer to a final continuous assessment process. This approach is controversial and incomplete as it only relies on student performance, leaving aside the teaching process (Carle, 2009; Griffin, 2004; Remedies & Lieberman, 2008; Stieger & Burger, 2010). Following Dickey and Pearson (2005), this final evaluation can be clearly contaminated by different aspects: facts and latest content, or by first impressions of teachers and / or the subject. In Europe in general and Spain in particular, within the new guidelines for university teaching arising from the process of convergence of higher education, the movement from a final evaluation towards procedural models is gaining momentum (López Pastor, 2012).

We agree with Kassens-Noor (2012) in thinking that Twitter can be a tool that fits this type of continuous and formative teaching evaluation. Its advantages are that it is based on microblogging (sending and publishing short messages) and that it is quick to read (no more than 140 characters), dynamic (information available in real time), accessible (for almost any device that connects to the network), functional (allows images, videos and links to other content to be embedded), organized (using hashtags representing subjects and ordered by date of publication), interactive (allowing users to see the posts of others, follow them, reply, share their messages through retweets or save them by marking them as favourites), non-invasive (not an IM chatline) and anonymous if desired (using nicknames or depersonalized nicknames) (Arana, Cabezudo, Morais, & Peñalba, 2012; Guzman, Del Moral, & González, 2012; Bernal, Cascales, Clemente, & Izquierdo, 2012; Kassens-Noor, 2012; Wakefield, Warren, & Alsobrook, 2011; Welch & Bonnan-White, 2012; Toro, 2010).

Studies on the use of social media in higher education are still scant and show some controversy. Calabuig and Donaire (2012), in their analysis of Twitter as a tool for participation and knowledge, concluded that the use of Twitter in the classroom was very positive, since for most students it was a useful methodological strategy and interesting for developing basic skills in higher education. However, Espuny, González, Lleixà, and Gisbert (2011), in their study on the attitudes and expectations of the educational use of social networks in college students by asking them about their views, found that although they were very familiar with and favourable to the incorporation of social networking, they saw little pedagogical use for this tool in higher education.

Moreover Kassens-Noor (2012), on research conducted to evaluate Twitter as a teaching practice to improve active and informal learning in higher education, warns us that in the specific case of Twitter, it could present some limitations over other methods; the reduced number of characters, for example, which may be an advantage depending on the intended use, can mean an impediment that restricts students’ broad and deep reflections. In the same vein, Toro (2010), from his analysis of the uses of Twitter in higher education, also adds, as a limitation to this tool, the distraction factor that it may have for some students since it can also be used as a social network. It can become addictive and the intended scholarly or educational value is lost. In addition, if students are not convinced of the pedagogical usefulness and benefits that its proper use in the classroom can bring, there will likely be a degree of resistance to its implementation and thus the benefits of its utilization will be clearly diminished (Lowe & Laffey, 2011; Rinaldo, Tapp, & Laverie, 2011).

Another benefit of the use of Twitter is that it overcomes the spatial and temporal boundaries of the classroom, extrapolating the debates of the contents of the subject outside the class, which is useful for internalization, identification and socialization of learning, even for the development of skills such as writing and synthesis, as well as interaction and collaborative work between students and teachers (Calabuig & Donaire, 2012; García Sans, 2009; Moguel, Alonzo, & Gasca, 2012; Toro, 2010). Wakefield, Warren, and Alsobrook (2011), in their work on how the network of real-time Twitter can arouse reflective thinking and communication, conclude that the tool fostered the understanding of materials, communication and promoted student learning.

In the study by Junco, Heiberger, and Loken (2011), done on 125 students to determine whether the use of Twitter as an educational tool helps engage students and mobilize teachers in a more active and participatory way, they found that participation and involvement was greater in the group using Twitter than in the group not using it, and that students who used the platform achieved better qualifications.

Welch and Bonnan-White (2012), in an investigation of 205 college students, found no significant differences in levels of involvement and commitment among students who used Twitter in the classroom and those who did not, and they asserted that those students who enjoyed using Twitter performed better in terms of their perception of commitment and participation.

We want to draw attention to the lack of specific studies on the use of Twitter to evaluate the teaching process. Only Kassens-Noor (2012) comes relatively close to it in his research conducted around the class diary, which recognizes that despite the limitations of the software, Twitter can be a useful tool to evaluate the development of the teaching process.

The possibility of improving teaching and learning during the class itself through the use of social networks led us to propose this research in which the value of Twitter as an evaluative tool in the process is analysed. Specifically, we set as our objectives: to assess the learning process (content, methodology and teacher intervention) of an undergraduate course, and to describe and interpret the students’ perceptions of the use of Twitter as a tool for participation in the university education process.

2. Method

Methodologically we have relied on a qualitative design based on the analysis of data produced (Cuñat, 2007; Strauss & Corbin, 2002) and the grounded theory of Glaser and Strauss (1967), supplemented with a descriptive analysis of frequencies.

The research involved a total of 146 students belonging to three groups of the subject of Teaching Physical Education in Elementary Education, given in the second year of the master’s degree in Elementary Education at the University of Granada, Spain. Student participation was voluntary and they were previously and fully informed of the research objectives and the importance of immediacy in sending the tweet at the end of the class or for it to be available on Internet. Anonymity was provided through a common account for those students wishing to keep their identity private.

Two data collection instruments were used: Twitter, to obtain feedback from students on the activities developed in the classroom, and a questionnaire with three questions, two closed, which assessed their perception of participation in Twitter from 1-4 in relation to the subject and the overall value placed on its use in the classes; the third was open, each student was free to reflect his or her views on the implementation and use of Twitter in the subject.

Data collection through Twitter was done either from a joint account or the students’ own accounts. At the beginning of each week, the teachers issued a tweet in which they reminded the students of the hashtags to be used to collect the opinions of each of the classes. There were a total of 30 (5 lectures, 11 practical classes, 11 occasions for dialogues, 2 days of theoretical presentation by the students, 3 tutorials and one day of shared assessment). There was no specification or limitation on issuing tweets, participation in each class was therefore different; students were only given information about the utility their feedback would have to improve the course, without it having any effect on their evaluation and qualification. This made disinterested participation possible, and free and honest opinions were sought.

Qualitative data was compiled and organized for analysis and processing using NVivo 10 software. The analysis process followed, based on grounded theory, with an inductive initial phase from an open or in vivo coding, in which the students identified the ideas and concepts and that had high interpretative significance. Later, in a more deductive phase, the central categories that would be the focus of the analysis were defined. Different indexing trees to deal with each of the targets in a simple and rigorous way were set. Finally we made comparisons using coding matrices and attribute crosses that enabled us to make graphs to illustrate the report. The analysis of the questionnaire was made by describing frequencies, enriched by the qualitative analysis of the views presented in the open question, following the same process described above for the qualitative analysis.

3. Results

We should note that the students contributed a total number of 495 tweets, an important quantity representing approximately 18% of total tweet potential that could have been received if each student had sent one for each class received, with attendance of around 75%.

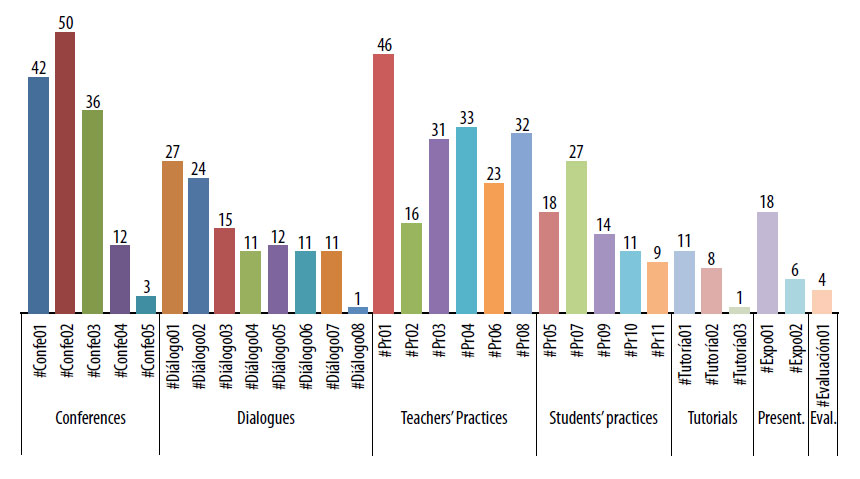

Based on the number of tweets (Chart 1) we can see how participation occurs mainly around the activities dedicated to conferences and to practical classes, especially those directed by teachers. By contrast, group tutorials and students’ theoretical presentations had the lowest values, together with the final sessions dedicated to the shared evaluation. Finally, we must highlight the progressive loss of participation in classes dedicated to dialogue activities.

Chart 1. Number of tweets in each class organized by hashtags

3.1. Evaluation of the teaching process

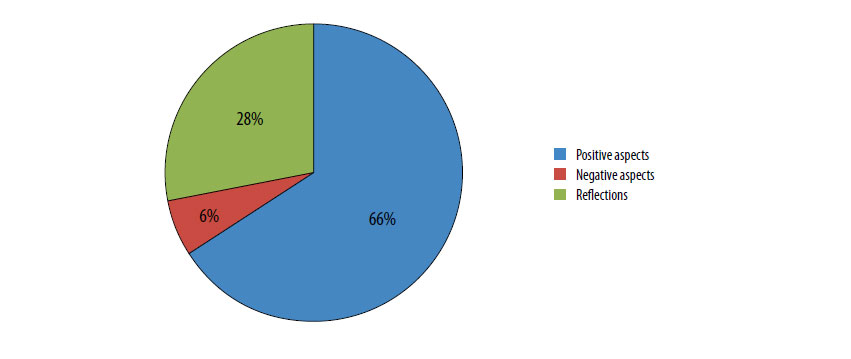

The first objective was to determine the overall assessment of the entire teaching process and make our own reflections about the usefulness of Twitter. To do this, the students’ tweets organized by classes through hashtags were classified into three categories according to whether they made reference to positive or negative aspects or did not make a direct reference to an assessment of the class, but rather reflected on the content given (Chart 2).

Chart 2. General evaluation of the classes according to the percentage of references

Sixty-six percent of the comments made allusions to positive aspects of the subject, and only 6% of the tweets criticized some nuance that should be improved or said that it was unwise. The remaining percentage corresponded to areas not directly related to evaluation; these gave personal reflections on an issue, question or experience stimulated by the content of the class.

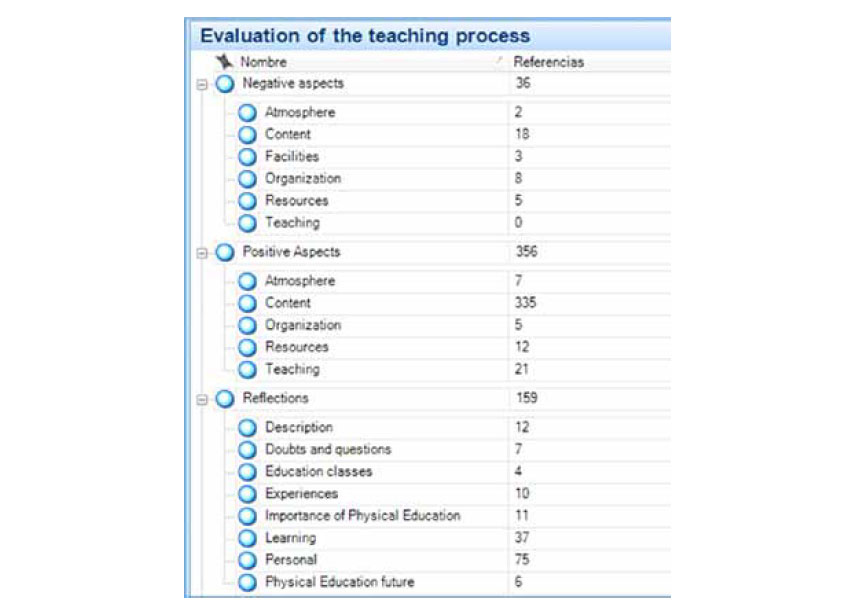

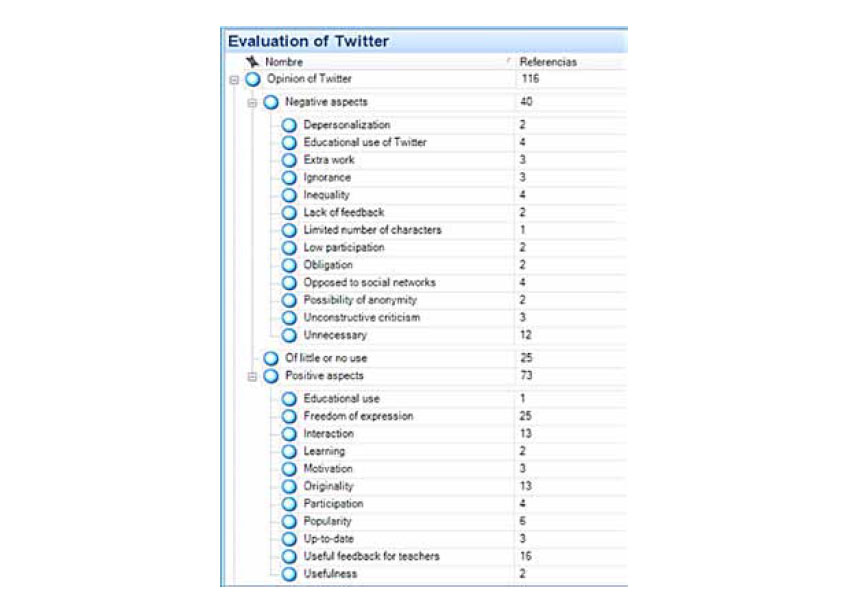

For a more detailed analysis of the content of the tweets, we divided the categories into subcategories (Figure 1). The majority of the comments made a positive assessment of the content, mainly expressing general satisfaction with remarks such as ‘amazing ...’, ‘Very interesting ...’, ‘... injected motivation’, etc.

Figure 1. Coding of tweets issued

We found that many of the tweets made no reference to any particular aspect of evaluation, but reflected underlying ideas of the class itself, most of which were along the lines of ‘we must accept and love ourselves as we are.’

Finally, the references in the comments on the negative aspects, far fewer in number, were mostly related to the content given. Some of them put a positive aspect with a negative one, such as: ‘As the first contact with the subject, it was in my opinion good, although too much information was included.’ A few users clearly reflected dissatisfaction with some aspect: ‘It is clear that I did not like the class much, it went out of our hands!’ Negative comments about the organization were mainly related to time, punctuality or some other specific organizational aspect, ‘the class was good but not how it was led, the same people always spoke and when others wanted to talk they did not let them’ .

3.2. Evaluation of Twitter as a tool for participation in the university education process

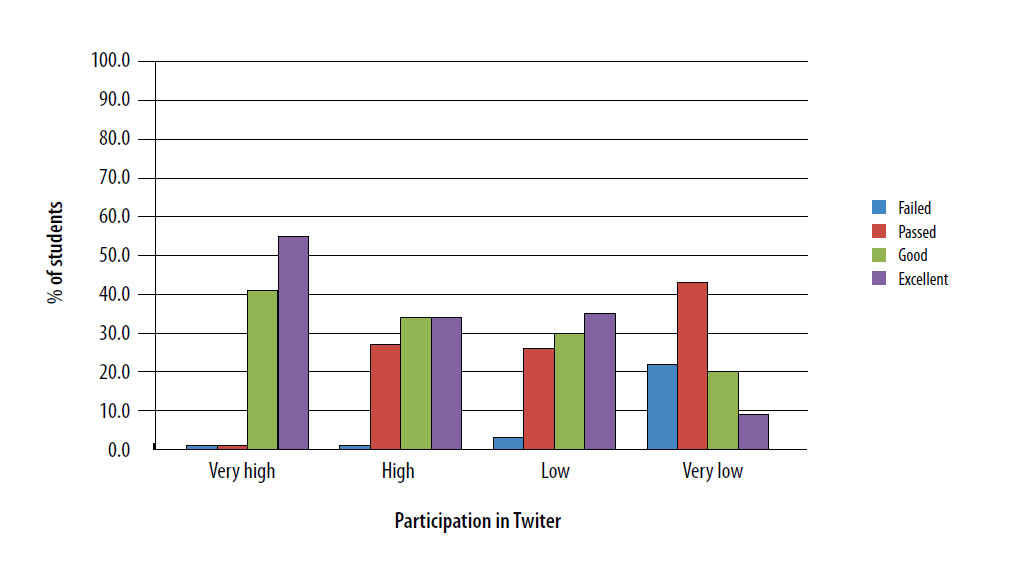

As is clear from their responses, it has to be borne in mind that 9% of the students considered their participation as deficient because they had never used Twitter at any time or on any specific occasion, and 30% said they had seldom used it. Therefore, it seems that the remaining 61% made use of the tool proficiently (Chart 3).

Chart 3. Twitter assessment based on participation

The trend in participation changes depending on the participation when making the evaluation of Twitter for the intended purpose. Thirty-three percent of the students welcomed the use of the tool, describing it as good and excellent compared to 28% who valued its use negatively, while the remaining 39% simply approved of its use.

Crossing the data of evaluation and participation in Twitter, we found that the students who least valued the use of Twitter in education were those who took little or no part in it. It is worth noting that a high percentage of students who still perceived their participation as scant (passed) nevertheless gave a high score (good or excellent) to its use in the course. Those students who perceived their participation as high or very high did not list failure as a mark, and good and excellent are the predominant scores.

The views expressed by students in the open question about using Twitter mainly made positive references (Figure 2). Most of them remarked on the freedom of expression that it allowed them, and being able to share ideas with peers, ‘with Twitter I found a way to express freely what we felt about the classes.’

The second most referred-to aspect in the positive comments was teacher feedback, i.e., the usefulness of the tool to inform teachers of their strengths and the weaknesses they should improve in each class: ‘Twitter has been a great help to the teachers, because our opinion is of great importance in that subject.’

Figure 2. Coding of comments on Twitter

Innovation is also highly valued. Many opinions spoke of the originality of the idea and appreciated the novelty and intention to do something different, ‘It’s new to me and I think for all my fellows [...] it seems like a great idea to motivate us.’ In addition, the students perceived very positively the ability to interact both with peers and with the teachers that allowed them to ‘... maintain direct contact between students and teachers.’

Although to a lesser extent, a considerable number of references in the evaluations mentioned the weaknesses and disadvantages of using Twitter in teaching. Forty ratings contained some comments about its shortcomings. Of these, the majority judged Twitter as unnecessary for the subject. Some cases considered that the benefit of its use was intended for teachers whereas students obtained no value from it: ‘the use of Twitter seems right for teachers to have an outside view of what is happening in their classes, but I do not see it as really useful for students.’

Other sources of dissatisfaction are inequalities that can be created according to whether or not one owns an account on the platform, or has greater or lesser skill in handling it, which excludes those students from participating in the process (‘... not everyone has it, and all students are no longer in the same conditions for participation’). Some students are opposed to social networks and to socialization through the network (‘I do not want more networks to socialize me ...’); others do not consider it a good teaching resource for incorporation into academia ‘as it is a social network, it is for more personal use’.

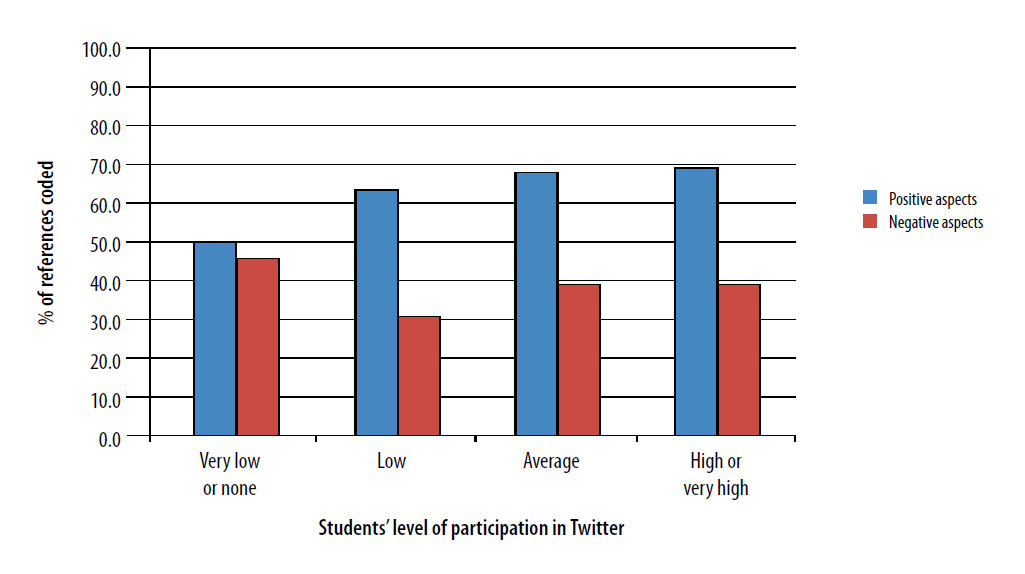

If we consider the effect of participation on the type of opinions, we see that the difference between positive and negative aspects gradually increased as the students’ participation increased (Chart 4).

Chart 4. Opinion on Twitter according to degree of participation

Thus, while those who barely used Twitter during the course discussed almost equally both the negative and positive aspects of the tool, students with greater participation showed considerable difference in favour of the positive.

4. Discussion

Regarding the assessment of teaching, from the evaluations of each of the classes, we can say that overall satisfaction has been high throughout the course. The students acknowledged having experienced an active methodology based on their sharing in the preparation and development of classroom activities. Moreover, we believe that the ‘poisonous pedagogy’ (Miller, 1998) of an evil named assessment may have adversely affected the level of global participation. Some students (it is a question we should research) have been inhibited from participating, despite having an anonymous account, for fear of having their opinions ‘controlled’ by the teachers, a symptom of the lack of democratic participation in the university classroom, or the prevalence of the outcome of the process, where students are only interested in what brings direct benefits to the final grade.

The freedom that Twitter offers to express opinions, sometimes far from the main objective, has opened another interpretive door in research, and enriched the processes lived in the classroom from a global viewpoint.

Most of the comments, both positive and negative, made reference to the content and theme of the class, highlighting its main virtues or criticizing those aspects disagreed with, either regarding its content or the way in which it was explained or worked. The high percentage of positive feedback leads us to interpret that overall satisfaction is high and therefore the path taken is in principle suitable.

We found that the students’ evaluation of Twitter as a tool for participation in the university education process was positive, but nevertheless there were numerous references against it. Among these difficulties, to a greater or lesser extent we have encountered all those put forward by Wakefield, Warren, and Alsobrook (2011) – rejection of social networks or discomfort with their use – and those proposed by Welch and Bonnan-White (2012), which, together with the above, highlighted the lack of familiarity or overload of accounts. In our experience, the criticisms were directed mostly towards consideration of the tool as unnecessary for the development of the subject. The failure to observe the direct impact of their participation and the zero impact on their course grade may have influenced this perception. Coinciding with the findings of Welch and Bonnan-White (2012), the experience was more positive in those students who reported having had a higher level of participation. Their estimates were always above good and their views in a large percentage alluded to the benefits of the platform. Students with little or no participation had a lower valuation of the use of Twitter (mostly approved) and a similar percentage of opinions regarding the advantages and disadvantages.

5. Conclusions

However, based on the results, we can conclude that Twitter as a tool for evaluating classes is broadly positive. The possibility of expressing views freely and taking part in the process of improving teaching the subject stand out. This strategy has proved to be very powerful and effective thanks to its spontaneity and immediacy. Yet, we think it should be complementary to a final deeper and more rigorous assessment. Its formative and continuing value allows us to approach the perspective of students, their views and interests, enabling us to act, change and improve the course at any time during the process. In addition, the proper use of Twitter to motivate the student can succeed in creating a sense of belonging and effective integration into the subject, and the student is considered as an active part of the process and identified with the results.

Of all the views and inputs obtained, we conclude that the addition of Twitter to the University academic level has been a positive and beneficial experience, being a popular and novel means that is usually well received by students. In those cases where the use of Twitter is rejected, we must ask whether it is specific to the tool or whether the problem is related to the teaching and learning proposed.

We detect that the tool has varied and valuable potentials different from those observed for its incorporation into our area and on which it would be interesting to continue researching, for example: to study the interest awakened in students by the fact of using an application that allows tweets with a certain hashtag to be shown in real time and to be projected in class while the teacher gives the class, or its use in sharing resources related to the topics covered in class; or the incorporation and visualization of tweets on the platform or website (Twitter for Websites) of the course to encourage student participation.

Finally, we must admit that part of the final success depends on students perceiving clearly the ultimate goal of using the tool and overcoming the simple instrumental view of Twitter. To achieve this, our experience tells us that the classroom should be democratized; the student should be granted equal status and freedom with the teacher and, from there, to promote an evaluation for improvement and learning that overcomes the sanctioning and hierarchical model that still prevails in the university classroom.