1. Introduction

Entrepreneurial activity is the driver of economic development at local, regional and national levels (Thomas & Mueller, 2000). In order to foster the skills needed to sustain a strong, more innovative and productive economy in years to come, many universities are encouraging students to pursue entrepreneurship education. This education is assumed to play a role in developing skills that increase individuals’ employability and, therefore, calls have been made for more studies to focus on assessing the impact of Entrepreneurship Education Programmes (EEPs) (Pittaway & Cope, 2007; Neck & Greene, 2011; Martin, McNally, & Kay, 2013; Walter, Parboteeah, & Walter, 2013). Since entrepreneurship education is developing at a rapid pace, it is time to take stock and monitor the impact of EEPs in order to adequately foster entrepreneurship (Kourilsky & Walstad, 2007; Alves & Raposo, 2009).

This study evaluates the impact of the programme “Generation of Innovative Ideas and Entrepreneurial Projects Development” (which will hereafter be referred to as “Entrepreneurs”) on the participants’ entrepreneurial beliefs, attitudes and intentions. For this purpose, we chose Ajzen’s (1987) Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB) model as an evaluation tool to investigate potential variations in how the participants on the course perceived the environment and their entrepreneurial abilities, attitudes and intentions at the end of the course and in the medium term (six months after finishing it). Besides this, a control-group design was used to investigate the impact of participation in the programme. With this design, the research is intended to assess the effectiveness of the course in fostering entrepreneurial intention and its antecedents. This leads to two broad contributions. On the one hand, the discussion of the results for the case under study will enable academics to make decisions about the contents of their entrepreneurial programmes in order to improve future editions of their courses. On the other hand, the study evidences the need to evaluate the efficiency of the programmes in which policy-makers are investing to promote an entrepreneurial culture to make decisions that guarantee the efficient allocation of public funding.

The paper is structured as follows: in the first section, we review the literature about the importance of entrepreneurial attitude and education in entrepreneurial intention. The following sections describe the methodology used and the results obtained. Finally, the conclusions and implications from this research are presented.

2. Theoretical framework

The study was undertaken in a Spanish peripheral region, Castilla-La Mancha, where the objective of the university is to contribute to regional economic development and societal well-being of the population. In 2012, the unemployment rate was 30% for the entire population of 2.2 million inhabitants, and the figure rose to 56.7% for young individuals under the age of 25 years (these two figures were higher than in Spain as a whole, 25.8% and 54.8% respectively) (EPA, 2012). Therefore, the university has recognised the importance of preparing students to be more flexible and entrepreneurial in their attitudes as a response to an increasingly uncertain labour market. This resulted, in 2012, in the creation of the Office of the Vice-Rector for Transfer and Relationship with Firms, which aims to foster an environment in which an entrepreneurial spirit can thrive. In short, entrepreneurship has become embedded within the university, and this support is essential, especially when financial resources are constrained.

In this context, the “Entrepreneurs” extra-curricular course is offered by our university, with the sponsorship of regional institutions. The objective is to transmit to students the values of an entrepreneurial culture and help them to achieve the necessary education that will enable them to materialise their idea or project in a successful firm. All the students at the university and other interested individuals can take the course, which is 50 hours in length and taught over four weeks. The course is structured into three modules (Motivation, Creativity and Ideas Generation, and Developing a Business Plan). Its content is developed mainly through practical activities based on participative learning, in which the students internalise the different contents of the programme, either individually or in a group. However, once it finishes, the students are not provided with any practical activities or follow-up assistance.

When designing an EEP, the first choice is the objective of the programme that relates to our definition of entrepreneurship. Initially, entrepreneurship was conceived of as the creation of new ventures, but more recently there has been a shift towards focusing on a broader concept that understands entrepreneurship as a way of thinking and behaving (Kirby & Ibrahim, 2011). It is appropriate to adopt a broad definition of entrepreneurship focusing on developing entrepreneurial mindsets that individuals can mobilise throughout their careers, either by driving innovation within existing firms (intrapreneurship), by transforming new and old organisations into social ventures, or by creating new firms with economic purposes. According to Fayolle and Gailly (2008: 582), the “Entrepreneurs” course can be classified as a teaching programme in which the students engage in “learning to become an enterprising individual” since the aim is “helping individuals to better position themselves as regards entrepreneurship and to become more enterprising”. Training programmes in this category can influence the variables that are considered “antecedents” of the entrepreneurial intention and, therefore, can be designed and evaluated according to their impact on the participants’ attitudes and intentions towards entrepreneurial behaviour. That is, intention models can be used both as pedagogical guides and as evaluation tools of educative actions, aiming to develop entrepreneurial mindsets in individuals so that they can fully realise their potential through their actions. Previous literature has primarily used two socio-psychological models to explore attitudes and their antecedents (beliefs) with an impact on entrepreneurial intention. These are Shapero’s (1982) Entrepreneurial Event (SEE) and Ajzen’s (1987) TPB models, which are largely consistent with each other (Krueger, Reilly and Casrud, 2000). However, whereas the SEE focuses more on the individual (including a measure of the individual’s proactiveness), the TPB focuses more on the environmental context (including social support for the behaviour), the latter being selected for that reason. Therefore, the hypotheses are related to how the main constructs of the model (self-efficacy, entrepreneurial attitude, perceived environmental difficulties and entrepreneurial intention) evolve in the short and medium term as a result of the impact of the course.

Along these lines, several studies point out that when individuals undergo an entrepreneurship course, their more favourable perception of entrepreneurship as a career option can be attributed, at least partially, to an increase in self-efficacy (Chen, Green, & Crick, 1998; Wilson, Kickul, & Marlino, 2007), that is, to the belief in their own abilities to develop the necessary entrepreneurial tasks. Bandura (1997) states that the sources from which individuals develop confidence in their abilities are practice, moderated levels of failure and acquired experience from observing how others develop the task (vicarious experience). Furthermore, Mau (2003) suggests that once self-efficacy in any skill is internalised by the individual, confidence encourages the individual to accept greater challenges, and succeeding in them reinforces his/her perception of efficacy, creating a spiral effect that improves self-efficacy even more. Therefore, considering that the course’s practical activities based on participative learning are intended to strongly influence the perception of self-efficacy, it is hypothesised that:

Hypothesis 1: Participants’ self-efficacy levels increase sometime after completion of the course.

Values and norms predominant in the social environment may also have an influence on an individual’s propensity to start a business (Etzioni, 1987). Autio and Wennberg (2010: 3) observe that “social group influences on entrepreneurial behaviors above and beyond the effect of individual-level dispositions”, specifically norms of social peer groups, can have three times more impact on an individual’s entry into entrepreneurship than an individual’s own attitude. The attitudes and behaviour of demographically similar others can influence career choices simply through exposure. The students participating in the course are part of a social group that is clearly interested in engaging in entrepreneurial behaviour, and they forge social networks that are maintained after the course. Besides this, a spiralling increase in self-efficacy, obtained through entrepreneurship education, can cause entrepreneurial attitudes to increase over time. Therefore, we propose that:

Hypothesis 2: Participants’ entrepreneurial attitude levels increase sometime after completion of the course.

However, given that the “Entrepreneurs” programme does not have a period of practical implementation of the knowledge acquired or assistance for creating their own firm after the course, we propose that participants will perceive more barriers in the environment for their entrepreneurial endeavour after the course and, therefore, entrepreneurial intention will decrease. Our assumptions are based on results obtained by Martínez, Mora, and Vila (2007), who observed that young graduates perceived that their academic institutions focused on teaching methods that paid special attention to general concepts, theories and paradigms, but not on the direct acquisition of work experience (which was not facilitated). Moreover, those who became entrepreneurs rated certain aspects of their education less satisfactorily, such as practical orientation, work experience provided and achievement of the necessary conditions to facilitate their access to the labour market. Therefore, it is proposed that:

Hypothesis 3: Participants’ perceptions of the difficulties to be confronted in the environment increase sometime after completion of the course.

Hypothesis 4: Participants’ entrepreneurial intentions decrease sometime after completion of the course.

Some researchers propose that matched control groups need to be incorporated into the evaluation of education programmes (Storey, 1999; Westhead, Storey, & Martin, 2001). In this research, the students who volunteered for the control group were undertaking an elective subject in Entrepreneurship within the Business Administration degree. The elective subject is taught over a four-month period, two and a half hours per week. Therefore, in case of self-selection bias, it should be present in both samples. Due to differences in the design of both courses, with the elective subject involving less intensive training and a more traditional teaching approach, we hypothesise that:

Hypothesis 5: Participants’ self-efficacy and entrepreneurial attitude scores are higher and the perception of difficulties in the environment is lower than for non-participants (at both moments in time).

Hypothesis 6: Participants’ entrepreneurial intentions are higher than non-participants’ (at both moments in time).

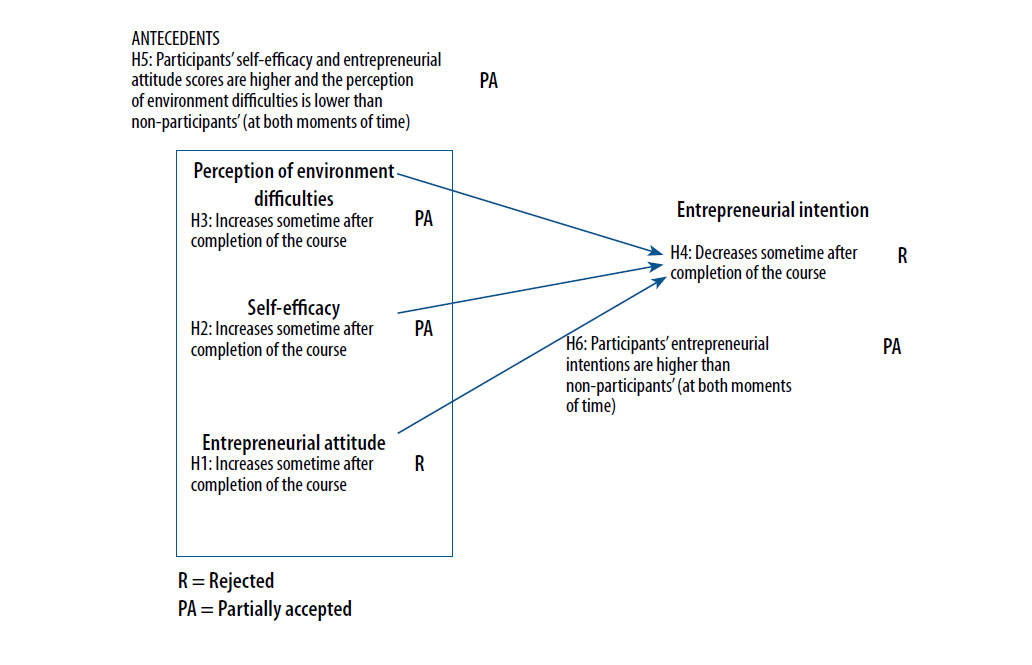

The model is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. ncidence of antecedents on entrepreneurial intention

3. Methodology

Several recommendations were followed when designing this training evaluation (Storey, 1999; Westhead et al., 2001). First, a representative sample of participants should be used. In this edition of the “Entrepreneurs” course, the number of participants in the course was 170 and, of these, 70 voluntarily answered the first questionnaire when finishing the course and 54 answered the follow-up questionnaire six months later (41.2% of the total answered the first one and 31.76% answered the second one). The sample (shown in Table 1) is representative of the studied population. As can be observed, the sample is balanced in terms of gender, and the majority is under 23 years old, studying Business Administration and not juggling studies with paid employment. A response bias test revealed no significant differences between respondents at different campuses with respect to students’ age, gender or occupation.

|

Gender |

Female |

Male |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

48.1% |

51.8% |

||||

|

Age |

Between 18 and 23 years old |

Between 24 and 29 years old |

Between 30 and 48 years old |

||

|

54.7% |

37.8% |

7.5% |

|||

|

Studies |

Business Administration |

Humanities |

Sciences |

||

|

59.6% |

21.2% |

19.2% |

|||

|

Occupation |

Student |

Employee |

|||

|

75% |

25% |

||||

Second, a matched control group has to be incorporated. All students undertaking the elective subject on “Entrepreneurship” filled in the questionnaire in the class (70), but only 23 of them volunteered to fill in the second one (six months later), which accounts for a 33% response. Eight of them were male and fifteen female, aged between 19 and 25 years (the average is 21.5 years old). T-tests were conducted to see whether there were any significant differences in scores between participants and non-participants in the “Entrepreneurs” programme.

Third, pre and post (programme participation) testing should be carried out. In our study, two points of time were studied, since we carried out post-programme testing at both the end of the course and six months after it. In order to identify any statistically significant change in the variables in the same group in two different moments of time, we used the Wilcoxon test (Cooper & Lucas, 2006). We acknowledge that the change might have been caused, at least in part, by external events or individuals’ tendencies. However, it is proposed that it would be difficult to attribute the existence of a change to any external factor, other than the course, since the majority continues studying six months later, having yet to confront the creation of their own firms.

Finally, objective as well as subjective outcomes should be measured. This last condition was not adhered to, since the programme does not imply the creation of a firm by the participants and, therefore, we could not measure objective outcomes. Entrepreneurial training is seldom followed by actual start-up activities and, therefore, intentions have been widely used as a proxy for evaluating the impact of training. The questionnaire, tested in a previous study published by the authors, contained questions relating to those cognitive variables that influence entrepreneurial intention.

Desirability and feasibility of creating their firms: Measured using a seven-point Likert scale. A descriptive analysis has been made of these variables, although they are not included in the model.

Entrepreneurial self-efficacy (Table 2): We used subscales obtained from earlier studies that establish entrepreneurial self-efficacy scales, with a ten point-Likert scale, in line with previous research (Kolvereid & Isaksen, 2006). We chose the subscale of risks assumption by Chen et al. (1998), the subscales of new products and market opportunities development and coping with unexpected situations by De Noble, Jung, and Ehrlich (1999) and the subscale of economic management by Anna, Chandler, Jansen, and Mero (1999).

Entrepreneurial attitude (Table 3): Degree to which the founder is committed to the new business in comparison with other alternatives that may be attractive for him/her and how much he/she is willing to sacrifice in order to become self-employed, that is, his/her intention to invest time and resources. Scale by Liao and Welch (2004) on a five-point Likert scale.

Perception of the environment (Table 4): The scale by Grilo and Thurik (2005) with regard to individuals’ perceptions of the difficulties in the environment was measured using a five-point Likert scale.

Entrepreneurial intention (Table 5): Four-item scale by Cooper and Lucas (2006) using a seven-point Likert scale.

4. Results

The results in Table 2 show that the self-efficacy levels in the diverse abilities were high after the course. Participants had internalised the acquisition of these abilities and this raised the probability of knowledge being transferred to new behaviours. Besides, a positive change can be observed from the end of the course to the follow-up moment in several abilities, supporting Hypothesis 1, at least partially.

|

|

% good to excellent |

Wilcoxon test Z (sig.) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

At the end of the course |

After six months |

||

|

1. I can work productively under continuous stress, pressure and conflict |

54.9 |

57.4 |

NS |

|

2. I can tolerate unexpected changes in business conditions |

56.9 |

63.0 |

-2.054b (0.040) |

|

3. I can develop and maintain favourable relationships with potential investors |

86.3 |

79.6 |

NS |

|

4. I can see new market opportunities for new products and services |

64.7 |

75.5 |

-2.508b (0.012) |

|

5. I can manage cash-flow (profits + amortisations + provisions) |

66.7 |

66.7 |

NS |

|

6. I can control business costs |

68.6 |

81.5 |

NS |

|

7. I can persist in the face of adversity |

63.3 |

71.2 |

-2.215b (0.027) |

|

8. I can discover new ways to improve existing products |

74.5 |

79.6 |

NS |

|

9. I can develop relationships with key people to access capital sources |

78.4 |

77.8 |

NS |

|

10. I can identify new areas for potential growth |

70.0 |

70.4 |

NS |

|

11. I can design products that solve current problems |

62.7 |

66.7 |

-1.740b (0.082) |

|

12. I can take decisions under uncertainty and risk |

64.0 |

68.5 |

-3.016b (0.003) |

|

13. I can bring product concepts to market in a timely manner |

58.8 |

63.0 |

NS |

|

14. I can learn everything I need to create a firm |

98.0 |

92.6 |

NS |

|

15. I can create products that fulfil customers’ unmet needs |

80.4 |

79.2 |

NS |

|

16. I can take risks in a calculated way |

72.5 |

72.2 |

NS |

|

17. I can assume the responsibility of ideas and decisions |

90.2 |

84.9 |

NS |

|

18. I can determine what the business will look like |

84.0 |

94.4 |

NS |

|

19. I can do the required tasks to make my firm a good start-up |

88.0 |

80.8 |

NS |

|

20. I can identify potential sources of funding to invest in the firm |

70.0 |

75.5 |

NS |

|

21. I can manage expenses |

78.0 |

86.8 |

NS |

NS= not significant

b= based on negative files, those that contain the cases in which the value of the variable in the second observation exceeds the value in the first one

With respect to entrepreneurial attitude, the levels were very high at the end of the course and had been maintained after the six months period (Table 3). Here, there is no support for Hypothesis 2 concerning an increase in entrepreneurial attitude after the course, since the high level had been maintained.

|

|

% of those who agree or totally agree |

Wilcoxon test Z (sig.) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

At the end of the course |

After six months |

||

|

1. I would prefer to have my own business than to earn a higher salary as an employee |

47.1 |

52.8 |

NS |

|

2. I would prefer to have my own firm than any other promising career |

33.3 |

28.3 |

NS |

|

3. I am predisposed to make personal sacrifices to keep my firm going |

68.6 |

59.3 |

NS |

|

4. I would do another job only for the time that I needed to in order to create my own firm |

58.8 |

56.6 |

NS |

|

5. I am predisposed to work for the same salary in my own firm as that of an employee in another firm |

78.4 |

64.8 |

NS |

Furthermore, Table 4 shows that the perception of difficulties confronted in the environment had worsened after the six-month period. The literature emphasises that one of the main dissuasive elements for firm creation is an inadequate knowledge of the process and the perception of risks (Oakley, Mukhtar, & Kipling, 2002). Therefore, Hypothesis 3 is supported, suggesting the need to eliminate these perceived barriers through the programme’s delivery as a crucial point in order to foster entrepreneurial motivation.

|

|

% of those who disagree or totally disagree |

Wilcoxon test Z (sig.) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

At the end of the course |

After six months |

||

|

1. It is difficult to create a firm due to a lack of financial support |

17.6 |

18.5 |

-1.737b (0.082) |

|

2. It is difficult to create a firm due to the complexity of administrative procedures |

17.6 |

40.7 |

-2.678b (0.007) |

|

3. It is difficult to obtain enough information about the process of creating a firm |

54.9 |

75.9 |

-1.798b (0.072) |

|

4. One should not create a firm if there is a risk that it will fail |

52.0 |

58.5 |

NS |

|

5. The present economic climate is not favourable to those wishing to create their own firm |

34.0 |

25.9 |

NS |

With respect to entrepreneurial intention (Table 5), only one item had increased after the course and this was related to thinking frequently about ideas and ways to create a firm. The spiralling growth in confidence in their skills may have formed an “entrepreneurial alertness” within these individuals that led them to be more receptive to the identification of opportunities in their environment and more creative to transform them into entrepreneurial ideas. Hypothesis 4 cannot be supported, since there was no decrease in entrepreneurial intention sometime after completion of the course.

|

|

% of those who agree, agree very much or totally agree |

Wilcoxon test Z (sig.) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

At the end of the course |

After six months |

||

|

If I see the opportunity to create a firm, I will make the most of it |

88.5 |

83.3 |

NS |

|

The idea of firms with high risk/high reward attracts me |

50.0 |

52.8 |

NS |

|

I frequently think about ideas and ways to create a firm |

63.5 |

74.1 |

-2.511b (0.011) |

|

Someday I will try to create my own firm |

76.9 |

77.8 |

NS |

|

Entrepreneurial intention (average on a seven-point Likert scale) |

5.05 |

5.25 |

NS |

After assessing the evolution of those who had participated in the programme, we proceeded to compare them with the control-group. The study found that participants in the “Entrepreneurs” programme had higher levels of self-efficacy and entrepreneurial attitude at both moments in time than non-participants. The participants in the programme also had a less optimistic perception of the economic climate, although this difference disappeared in the follow-up questionnaire. Entrepreneurial intention was significantly higher for the participants in comparison to the control group after the six-month period. Therefore, Hypotheses 5 and 6 are supported, at least partially. One reason for these results might be the importance of practical training provided on the “Entrepreneurs” course versus the more traditional lectures on the degree subject.

5. Conclusions

Our research question was: What is the impact of the “Entrepreneurs” course on participants’ entrepreneurial beliefs, attitudes and intentions? To answer this question we designed the study using the TPB model as a course evaluation tool; testing two moments in time and comparing the course participants with a control group. The results suggest that the course encouraged participants to develop, even after the course, entrepreneurial self-efficacy and a perception of entrepreneurship as a desirable career option, with a medium-high level of entrepreneurial attitude and intention both in the short and medium term.

However, although almost all participants perceived the entrepreneurial option as highly desirable (92.2%), only half of them perceived it as highly feasible (53.8% and only 41.5% after six months), and their perceptions of the difficulties that have to be confronted in the environment worsened over time. These findings suggest that focusing on “Developing a Business Plan”, although practical in nature, did not provide participants with the direct experience in entrepreneurship that they would need to go from intention to action.

We consider that our study contributes to scholarly knowledge on two levels. First, with regard to designing an effective teaching programme, in which there is an interrelation between the objectives, the contents and the methodologies used to deliver them. With regard to the programme objective, it is advisable to consider a broad definition of entrepreneurship focusing on developing entrepreneurial mindsets which individuals can mobilise throughout their careers, either through intrapreneurship or their own firms. The programme under review, although recognising the importance of building an entrepreneurial mindset as a learning objective, still places considerable importance on the creation of new ventures, focusing on how to develop a business plan. Methodologies are selected contingent on the programme’s objectives. In comparison with the control group, participants in the “Entrepreneurs” course had greater self-efficacy and entrepreneurial attitudes and intentions and more perceptions of environmental difficulties. These findings underline the importance of using a practically oriented and participative learning approach. However, as stated previously, we consider that more emphasis on the value of “experience” and the “experiential learning” approach has to be included in future editions of the course. Our proposals are the following: providing participants with follow-up assistance for creating their own firms; establishing practical placements in firms that are starting up or have recently been created to obtain vicarious experience and/or inviting entrepreneurs to come to the classroom. Previous literature has evidenced that an extra-curricular course has better results when it includes practical placements in firms, especially with respect to the maintenance of a positive change in entrepreneurial intention (Cooper & Lucas, 2006). Besides this, students can learn from those who have first-hand experience of firm creation: how failure can be overcome, how to confront difficulties and how to persist in the face of important challenges (Fayolle & Gailly, 2008; Cooper & Lucas, 2006).

Second, with respect to entrepreneurial training evaluation, the findings indicate that the TPB is an appropriate theory to test the effectiveness of an entrepreneurship course that aims to promote entrepreneurial mindsets. We consider that a better knowledge of how entrepreneurial training impacts on cognitive variables is needed in order to adjust educational curricula to serve potential entrepreneurs and also to make an efficient use of those public resources allocated to foster an entrepreneurial mindset. If we achieve the reinforcement of students’ perceptions not only of self-efficacy in entrepreneurial tasks but also of the environment, we will be able to observe an increase in entrepreneurial intention that might be translated into more entrepreneurial behaviour, which has to be appropriately sustained over time.

Our study also has some limitations for which we propose suggestions for further research. Since previous literature has shown that entrepreneurial-related attitudes and abilities exert a significant influence on entrepreneurial activities (Arenius & Minitti, 2005; Koellinger, Minniti, & Schade, 2007), the study analysed the antecedents of entrepreneurial intention on a sample of university students. However, we acknowledge that trying to motivate students to become entrepreneurs is a long-term and challenging endeavour. In this programme, however, there was no follow-up of their career paths afterwards. For this reason, as a future line of research, we propose designing a study that assesses the persistence of entrepreneurial intention and its antecedents after a longer period of time, controlling for events in participants’ lives.

Besides this, future studies need to address the possibility of self-selection bias, since students who voluntarily engage in entrepreneurship training are more likely to be thinking about starting a business. However, we do not have the possibility of dealing with a compulsory programme to avoid that bias. Another limitation of this study was that participants did not fill in a questionnaire before entering the course; this information would have been useful to test the impact of the programme according to the initial level of intention. Nevertheless, due to the exploratory nature of this study, it can be assumed that the course at least had an important impact on the participants’ perceptions, which had been maintained in many variables after a period of time. This study was limited to a single cohort of students at a single institution. Future studies should address the sampling issue by taking into account the moderating effect of previous entrepreneurial experience, socio-economic status or context on the impact of education programmes on entrepreneurial intentions.